Contents

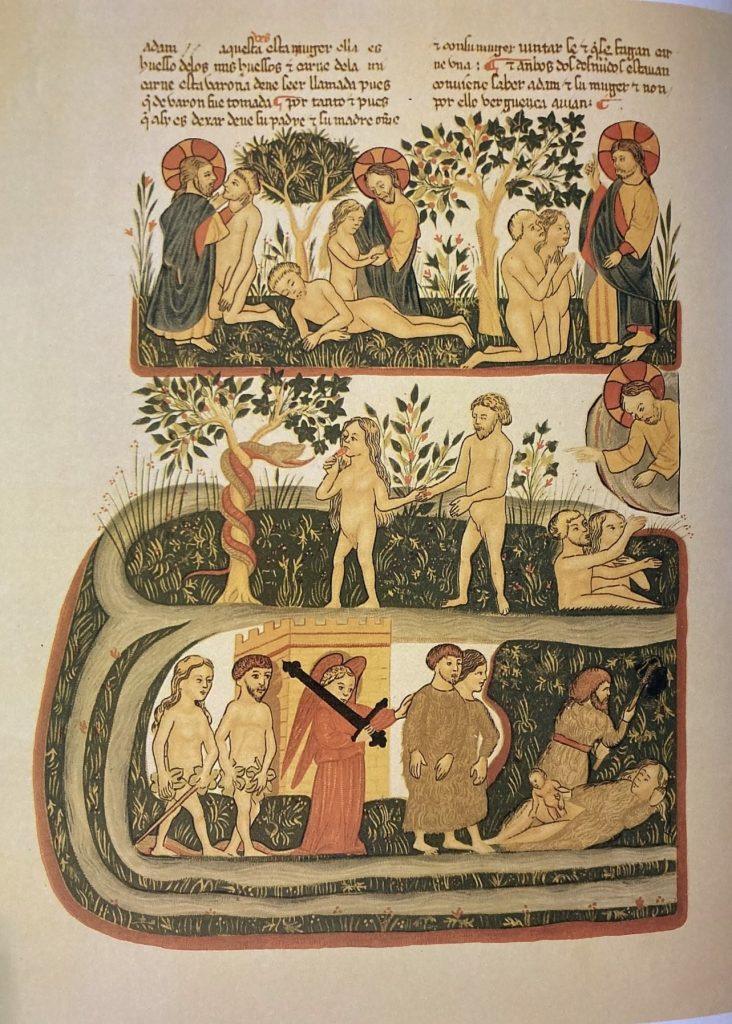

Before the expulsion of Jews from Spain in 1492, Spanish Jewry thrived as one of the most significant and culturally rich Jewish communities in the world. Known as Sephardic Jews, they had a distinct culture, language, and identity deeply intertwined with the Iberian Peninsula.

The Sephardic Timeline

SephardicU has constructed a comprehensive and visually interactive timeline of the rich Sephardic heritage.

Thriving Under Muslim Rule

Jews had lived in Spain since ancient times, with substantial populations during the Roman and Visigothic periods. However, it was under Muslim rule, which began in the early 8th century with the Umayyad conquest of Hispania that Jews were really able to flourish. The conditions for Jews in Spain improved so much under Muslim rule that Jews migrated to Spain from Europe and North Africa. It became the largest Jewish community in the world.

Jews excelled in various fields including philosophy, science, medicine, and poetry. They held positions of influence in government, commerce, and academia, contributing to the rich tapestry of Andalusian society.

The Jews were outstanding doctors and served the medical needs of both Jews and non-Jews including the leaders of Spain. Among the most famous doctors were Maimonides, Nachmanides, Rabben Nissim of Gerona, and Rabbi Chasdai ibn Shaprut.

Short biographies of the famous Doctors / Rabbis in Spain

Maimonides

Moses Maimonides, also known as the Rambam, was among the greatest Jewish scholars of all time. He made enduring contributions as a philosopher, legal codifier, physician, political adviser and local legal authority. Throughout his life, Maimonides deftly navigated parallel yet disparate worlds, serving both the Jewish and broader communities.

Maimonides was both a traditionalist and an innovator. Although he endured his share of controversy, he nevertheless came to occupy a singular, unquestioned position of reverence in the annals of Jewish history.

Moshe ben Maimon was born in 1138. He grew up in Córdoba, in what is now southern Spain. Reared in a prosperous, educated family, the young Maimonides studied traditional Jewish texts like Mishnah, Talmud and Midrash under the tutelage of his father. He also studied secular subjects like astronomy, medicine, mathematics and philosophy — a medieval “liberal arts” curriculum, so to speak. He was particularly captivated by the Greek philosophers Aristotle and Plotinus; their ideas persuaded him that reasoned inquiry was not only reconcilable with Judaism, but in fact its central discipline. Blessed with a prodigious memory and ravenous intellectual curiosity, Maimonides adopted an expansive view of wisdom. He had little patience for those who cared more about the prestige of scholars than the merits of their assertions and admonished his students: “You should listen to the truth, whoever may have said it.” (Commentary on the Mishnah, Tractate Neziqin)

Maimonides lived under Islamic rule for his entire life, and he both benefited and suffered greatly because of it. Maimonides spent his formative years in a society in which tolerant Muslim leadership catalysed vibrant cultural exchange with its Jewish and Christian minorities. Islamic scholarship in particular influenced him, especially later in his life. Unfortunately, when Maimonides was 10 years old, a fundamentalist Berber tribe called the Almohads entered Córdoba and presented Jewish residents with three choices: conversion, exile or death. The Maimoni family chose exile, leaving Córdoba and eventually emigrating to Morocco in about 1160, when Maimonides was in his early 20s. Many scholars believe Maimonides may have outwardly practiced Islam during this period, not out of belief but in order to protect himself, and that he continued to practice Judaism secretly. In 1165, the Maimoni family set sail for Palestine. After a brief yet formative visit to the land of Israel, then under Crusader rule, they finally settled in Egypt in 1166 — first in Alexandria, and eventually in Fustat (part of present-day Cairo). Maimonides lived there until his death in 1204.

Mishneh Torah and Guide of the Perplexed

Despite his demanding schedule as a full-time physician, Maimonides wrote prolifically, composing philosophical works, ethical and legal response letters, medical treatises and, in his 20s, a commentary on the entire Mishnah. His most enduring masterworks are the Mishneh Torah and the Guide of the Perplexed. Although he wrote them at different times and for different audiences, modern scholars understand the MishnehTorahand Guide to be highly interdependent. They project a unified and reason-based vision of the purpose of Jewish life.

References and further reading

- Halbertal, Moshe, trans. Joel A. Linsider. Maimonides: Life and Thought. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 2014.

- Kraemer, Joel L. Maimonides: The Life and World of One of Civilization’s Greatest Minds. New York: Doubleday, 2008.

- Maimonides, Moses ( Isadore Twersky, ed.) A Maimonides Reader. New York: Behrman House, 1972.

- Stroumsa, Sarah. Maimonides in His World: Portrait of a Mediterranean Thinker. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 2009.

- https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/maimonides-rambam/

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Moses-Maimonides

- https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/moses-maimonides-rambam

- https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/who-was-maimonides/

- https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/maimonides

Nahmanides

Rabbi Moses ben Nahman (Nahmanides), also known by the acronym of his initials, Ramban, was a medieval Spanish Jewish rabbi and thinker who wrote famous commentaries on the Torah and the Talmud. He was also a philosopher, poet and physician. In addition to his commentaries on Jewish sacred texts, he left behind several codes of Jewish law, sermons, piyyutim (religious poems) and other writings.

Nahmanides was born in Gerona, Spain and lived there for most of his life. He was an influential member of the kabbalistic community, though he left few writings about Kabbalah. Late in life, he emigrated to the land of Israel.

Nahmanides’ commentary on the Torah is one of the standard commentaries printed alongside the Hebrew text, like those of Rashi and Ibn Ezra. Nahmanides often explained the p’shat, the simple meaning of the text, but he also sometimes gave longer philosophical comments and interpolated mystical interpretations. He envisioned the commentary as a synagogue companion, “To appease the minds of the students, weary through exile and trouble, when they read the portion on Sabbaths and festivals.”

Nahmanides was on good terms with Christian notables, including King James I of Aragon before whom he delivered a sermon that still survives. Famously, he participated in the disputation of Barcelona where he publicly debated Pablo Christiani, a man who converted from Judaism to Christianity and then denounced the former. The subject of the debate was whether or not Jesus was the messiah.

Alhough Nahmanides won the public debate, including 300 dinars of prize money, and wrote down his main points in a work that still survives today, Sefer Vikkuach, his participation made it impossible for him to remain in Catalonia. At the age of 70, Nahmanides was forced to flee Spain and went to Israel. Though he settled in Akko where he continued to write prolifically, he also helped re-establish the Jewish community in Jerusalem following its destruction by the Crusaders in 1099.

Sources and further reading

- Caputo, Nina, Nahmanides in Medieval Catalonia: History, Community and Messianism. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2008. Pp. 384.

- Joseph E. David, Dwelling within the Law: Nahmanides’ Legal Theology, Oxford Journal of Law and Religion (2013), pp. 1–21.

- https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/moshe-ben-nachman-nachmanides-ramban

- https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/111857/jewish/Ramban.htm

- Who Was Nahmanides (Ramban)?

- https://www.jewishhistory.org/nachmanides/

Hasdai ibn Shaprtu

Hasdai ibn Shaprtu was born around 915 in Jaen, Spain, two centuries after the Umayyad Caliphate wrested control of Iberia from the Visigoths. He studied the Talmud in his youth and became proficient in linguistics, while also becoming a prominent physician. He became the court physician of Caliph Abd ar-Rahman III, who recognized his talents and gave him the powers and responsibilities of a vizier without actually using the title. Hasdai would use his expertise to navigate various diplomatic and commercial activities, securing peace treaties and managing foreign affairs. He was also instrumental in translating a piece of pharmaceutical text by Dioscorides, converting the Greek work (a gift from a Byzantine envoy) into Arabic, thereby benefiting his patrons.

Aside from these things, Hasdai also used his power as the appointed leader of the Spanish Jews to strengthen Jewish scholarship in Spain, establishing academies and supporting writers and poets, establishing the groundwork for the Golden Age.

When the Caliph died and his son rose to power, Hasdai continued serving faithfully. Sadly, it was in Al-Hakim’s reign that Hasdai died, around 970.

Hasdai ibn Shaprut helped facilitate the Golden Age of Spain. He was a man of many talents, nurturing Jewish culture in his area of influence. He was also said to have sent a letter to Khazaria, hoping to find a Jewish kingdom there, showing an interest in discovering Jewish heritage in other places.

Further reading

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hasdai_ibn_Shaprut

- https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/112514/jewish/Hasdai-Ibn-Shaprut.htm

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Hisdai-ibn-Shaprut

- https://www.encyclopedia.com/religion/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/hisdai-hasdai-ibn-shaprut

- https://kosherrivercruise.com/hasdai-ibn-shaprut-scholar-and-translator/

Rabbeinu Nissim of Gerona (c 1290 – 1376)

Rabbeinu Nissim—known simply by the acronym “Ran”—was born close to the turn of the 14th century in the Kingdom of Aragon, one of several countries that made up the Spanish territory during the Middle Ages.

For most of his life, the Ran lived in Barcelona, one of the major centres of Spanish Jewry and headed a yeshiva and served as a judge at the rabbinical court of Barcelona. Although he did not accept an official position as a rabbi in the city, he was the leading authority and any matter of weight landed on his desk. He was deeply involved in communal affairs and received halachic queries from well beyond the borders of Aragon.

He studied medicine and became a renowned physician. In this capacity, and as an adviser to the king on various matters, he attended the court of Peter IV of Aragon. Records of a number of interactions between the Ran and members of the royal court still exist.

In the spring of 1348, the “Black Death,” also known as the bubonic plague, reached Catalonia. Over the next few years, it would wreak havoc across Europe, killing approximately 50% of its inhabitants. Predictably, Jews were wrongfully blamed, with widespread rumours accusing them of poisoning the water wells. While the authorities (including Pope Clement VI) attempted to quell these false reports, their efforts were largely unsuccessful. On the 17th of May, 1348, a mob attacked the Jewish quarter of Barcelona. They ransacked the synagogue and murdered some 20 people. After the communal leaders—including the Ran—petitioned the king, he dispatched soldiers to protect the Jews of Barcelona, and in 1349 he absolved them of any debt incurred as a result of the pogrom.

In 1367, the Ran and a group of prominent community leaders—including Rabbi Chasdai ben Abraham Crescas, Rabbi Yitzchak bar Sheshet, and his brother Yehuda—were arrested and imprisoned. It seems that they were the target of trumped-up charges pushed by a group of disgruntled community members. Notwithstanding the fact that the Ran had been in good standing with the Royal Court, they languished in jail for some five months. Eventually, the charges were dropped and they were set free.

The Ran’s magnum opus, and arguably his most studied work today, is his Commentary to the Sefer Halachot of the Rif (Rabbi Yitzchak Alfasi 1013–1103). The Rif’s Halachot was the first attempt to extract halacha from the Talmud in an organized way.

The Ran also penned a commentary on the Talmud, Chiddushim al Hashas. It seems likely that he wrote commentary on the entire Talmud, or a very significant portion of it, however only about 10 have survived. In addition to his extensive corpus of halachic and Talmudic commentary, the Ran also composed a highly influential work on Jewish belief and ethics, Drashot Haran.12

Sources and further reading:

- Leon A. Feldman, Rabennu Nissim: Biographical Highlights.

- Encyclopedia of Renaissance Philosophy entry for Gerondi, Nissim ben Reuben (Shalom Sadik)

Websites

Jews also served as ministers in the government. Rabbi Casdai served in the court of Abd-ar-Rahman III around the year 912. Rabbi Shmuel HaNagid excelled in the mastery of Arabic language, grammar, and literature which led him to the office of vizier. In addition to his involvement in government affairs, Rabbi Shmuel also served as the rabbi of a flourishing community, the director of the Yeshiva of Granada, and a supporter of Jewish scholars. Rabbi Shmuel Hanagid died in Granada in 1055 and was mourned by both the Jewish and Arab populations.

Jews also stood out in Torah study and many of the outstanding Torah leaders of the time resided in Spain. Great scholars who lived and taught in Spain and whose works are still studied today include Rabbi Yitzchak Alfasi, Ri Migash, Ramban, Rashba, Ritva, Rabbi Avraham Ibn Ezra, Rabbeinu Bachya ibn Pakuda and the remarkable poet, Rabbi Yehuda HaLevi.

Short biographies of great Torah scholars

Rabbi Yitzchak Alfasi

Yitzchak ben Jacob Alfasi was born in 1013, near Fès, Morocco and died in 1103 in Lucena, Spain. He was a Talmudic scholar who wrote a codification of the Talmud known as Sefer ha-Halakhot (“Book of Laws”), which ranks with the great codes of Maimonides and Karo.

Alfasi lived most of his life in Fès (from which his surname was derived) and there wrote his digest of the Talmud, the rabbinical compendium of law, lore, and commentary. In 1088 two of his enemies denounced him to the government on an unknown charge. He fled to Spain, where, in Lucena, he became head of the Jewish community and established a noted Talmudic academy. Alfasi motivated a rebirth of Talmudic study in Spain, and his influence was instrumental in changing the centre of such studies from the Eastern to the Western world.

His codification deals with the Talmud’s legal aspects, or Halakha (Hebrew Law), including civil, criminal, and religious law. It omits all homiletical passages as well as portions relating to religious duties practicable only in Palestine. He performed a great service by concentrating on the actual text, which had been neglected. His commentaries summarize the thought of the geonim who presided over the two great Jewish academies in Babylonia between the middle of the 7th and the end of the 13th century. In addition, his work played a major role in establishing the primacy of the Babylonian Talmud, as edited and revised by three generations of ancient sages, over the Palestinian Talmud, the final compilation of which had been interrupted by external pressures. Alfasi’s Sefer ha-Halakhot is still important in yeshiva studies.

Sources and further reading:

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Isaac-ben-Jacob-Alfasi

- https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/112338/jewish/Yitzchak-Ben-Yaakov-Hacohen-Alfasi.htm

- https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/rabbi-isaac-alfasi-rif/

- https://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/1191-alfasi-isaac-ben-jacob

Ri Migash

Joseph ibn Migash was born in Seville . He moved to Lucena at the age of 12 to study under the renowned Talmudist Yitzchak Alfasi (see above). He studied under Alfasi at Lucena for fourteen years. Shortly before his death (1103), Alfasi ordained Ibn Migash as a rabbi, and – passing over his own son – also appointed him, then 26, to be his successor as Rosh Yeshiva (seminary head). Joseph ibn Migash held this position for 38 years.

It is clear that Migash was a great scholar: Maimonides in the introduction to his Mishnah commentary says “the Talmudic learning of this man amazes everyone who understands his words and the depth of his speculative spirit; so that it might almost be said of him that his equal has never existed.” Judah ha-Levi eulogizes him in six poems which are full of his praise. Joseph ibn Migash’s best known student is probably Maimon, the father and teacher of Maimonides. In Maimonides’ Introduction to his Mishnah commentary, he heaps lavish praises upon Rabbi Joseph ibn Migash (Halevi), saying of him: “I have collected what I stumbled across from the glosses of my father, of blessed memory, as well as others under the name of our Rabbi Joseph Halevi, of blessed memory; and as the Lord lives, the understanding of that man in the Talmud is astounding, as anyone [can see] who observes his words and the depth of his comprehension, until I can say of him that ‘there has never been any king like unto him before him’ (cf. 2 Kings 23:25) in his method [of elucidation]. I have also collected all of the legal matters (Heb. halachot) that I found that belonged to him in his commentaries, themselves.”[2]

There is a tradition that Maimonides himself was a pupil of Joseph ibn Migash. This probably arose from the frequent references in Maimonides’ works to him as an authority. It is unlikely that he was literally taught by him, as Maimonides was 3 years old at the time of Joseph ibn Migash’s death.

However, Maimonides’ grandson published a pamphlet with the approval of his grandfather, in which it is described that Maimonides ran away from home in his youth, met Joseph ibn Migash, and studied under him for several years

Joseph ibn Migash authored over 200 responsa, She’elot u-Teshuvot Ri Migash – originally in Judeo-Arabic – many of which are quoted in Bezalel Ashkenazi’s Shittah Mekubetzet. Five of Ibn Migash’s responsa survived in Yemen, and were published by Rabbi Yosef Qafih in 1973. He specified Chananel Ben Chushiel and Alfasi as his authorities, but disagreed with Alfasi in about thirty some odd places related to Halacha.

He also authored a Talmudic commentary – ḥiddushim (novellae) on tractates Baba Batra and Shevuot (included in Joseph Samuel Modiano’s Uryan Telitai, Salonica 1795) – which is quoted by various Rishonim. His other works have been lost.

Sources and further reading

- https://www.sefaria.org/topics/joseph-ibn-migash?sort=Relevance&tab=sources

- https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/112051/jewish/Rabbi-Joseph-Ben-Meir-Ibn-Migash.htm

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_ibn_Migash

- https://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/8006-ibn-migas-joseph-jehosef-ben-meir-ha-levi

Rashba

Shlomo ben Avraham ibn Adret (Rashba) was a Spanish rabbi, talmudic commentator, legal decisor, and community leader in the 13th century. He lived his entire life in Barcelona.

He is considered the most outstanding student of Ramban and continued his teacher’s approach in talmudic exposition, authoring chiddushim (talmudic novellas) on many tractates which remain mainstays of Torah study to this day.

His yeshiva drew exceptional students from throughout the Jewish world, including many from Germany.

He functioned as chief rabbi of Spain and wrote over one thousand responsa to individuals and communities throughout the Jewish world.

He was involved in opposition to Rambam’s philosophical writings and prohibited the study of philosophy under the age of 25.

He also defended Judaism to Christian and Muslim polemicists.

Sources and further reading

- https://www.sefaria.org/topics/rashba1?sort=Relevance&tab=sources

- https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/111870/jewish/Rabbi-Solomon-Ben-Abraham-Adret.htm

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shlomo_ibn_Aderet

The Ritva

The Ritva, Rabbi Yom Tov ibn Asevilli, was the rabbi and head of the Yeshiva of Seville in Spain. Neither the exact year of his birth nor of his death is known, but a good approximation is that he was born in the 2nd half of the 13th century and that he died in the 1st half of the 14th century. It is known that he and his Yeshiva flourished around the year 1320.

He was the leading student of the Rashba and of the Ra’ah and was a “talmid muvhak,” a student very closely attached to the latter.

His commentary on the Talmud is known for its clarity of thought and of expression, and it is in very wide use throughout the Torah-learning world.

Many “she’elot,” questions regarding Jewish Law, were sent to him, even during the lifetimes of his great teachers. This shows that he was considered in his maturity by the Jewish world to be in the same “league” as they were; that is, he was on a similar level of Torah knowledge and ability to use that knowledge insightfully to apply it to questions that arose in his day.

Yom Tov’s reputation rests upon his novellae to the Talmud, Ḥiddushei ha-Ritba. He apparently began writing them from the direct dictation of his teacher Aaron ha-Levi. When, however, he realized that the work would be inordinately long, he decided to make an abbreviated version. His novellae are, in general, very rich in early source material: tosafistic, Spanish, Provençal, and geonic, and display a considerable originality, though he is very much under the influence of his two great teachers.

Sources and further reading

- Ishbili, Rabbi Yom Tov Ben Abraham (Alashbili – known as the Ritva c 1250-1330) edited by Rabbi Yosef David Kapach, Sheelot U’Teshuvot – Responsa of the Ritva – Published for the first time from a unique manuscript with introduction and notes by Rabbi Yosef David Kapach, Jerusalem, Mossad HaRav Kook 1959

- https://jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/15119-yom-tob-ben-abraham-ishbili

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yom_Tov_of_Seville#:~:text=Yom%20Tov%20ben%20Abraham%20of,his%20commentaries%20on%20the%20Talmud.

- https://jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/15119-yom-tob-ben-abraham-ishbili

Rabbi Avraham Ibn Ezra

Abraham Ibn Ezra was born in 1089. He was a poet, astrologist, scientist, and Hebrew grammarian. All the Hebrew grammar books to that time had been written in Arabic including Saadia Gaon’s famous work. When he discovered that the Jews of Italy didn’t understand Hebrew grammar, he wrote an excellent book in Hebrew which elucidated for Jews living in Christian Europe Hayyuj’s tri-letter root theory.

Ibn Ezra also introduced the decimal system to Jews living in the Christian world. He used the Hebrew alef to tet for 1–9, but added a special sign to indicate zero. He then placed the tens to the left of the digits in the usual way.

In 1040 Ibn Ezra left Spain and began travelling. His works record that he travelled to Italy, France, and England. He appears to have earned his living in these places by teaching the sons of wealthy Jews and, though of a fiercely independent temperament, he allowed himself also to be supported by a number of patrons of learning.

Ibn Ezra’s most famous work was his commentary on the Bible. Unlike Rashi, Ibn Ezra didn’t want to use midrash in his explanations. He concentrated on the grammar and literal meaning of the text. His most controversial beliefs were all couched in very careful language; scholars suspect that Ibn Ezra did not believe that the Torah was written by Moses on Mount Sinai. He found seams and grammatical problems which indicated that the Torah was written over a period of time. He didn’t dare proclaim this opinion openly; it would have meant his death. However, there are hints of his suspicions within his commentary. He carefully used the phrase, “And the intelligent will understand” whenever he discussed a controversial insight.

Although Abraham ibn Ezra was not a systematic philosopher, he presented philosophical positions in his biblical commentaries. He was essentially neoplatonic and was strongly influenced by Solomon ibn Gabirol.

Ibn Ezra divided the universe into three “worlds:” the “upper world” of intelligibles or angels; the “intermediate world” of the celestial spheres; and the lower, sublunar “world” which was created in time.

His images of creation powerfully influenced later generations of kabbalists.

Sources and further reading

- https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/abraham-ibn-ezra

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Abraham-ben-Meir-ibn-Ezra

- https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/111872/jewish/Rabbi-Abraham-Ibn-Ezra.htm

- https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ibn-ezra/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abraham_ibn_Ezra

Rabbeinu Bachya ibn Pakuda

Rabbi Bachaya (11th CE) lived in Muslim Spain, probably in Saragossa, and served as a judge, but little else is known about his life. He was thoroughly conversant with the entire Biblical and Talmudical literature and was also master of all the knowledge and science of his day.

Though a philosopher in his own right, Rabbi Bachaya’s essential contribution is that of creator of a new genre in Jewish literature, Jewish ethics. His magnum opus was entitled Duties of the Heart (Chovot HaLevovot) which was written in Arabic. The first chapter of this work is devoted to the unity of G-d and employs philosophical arguments which some felt were not readily understandable and was skipped over by many students. Rabbi Bachaya’s work, as indicated by its title, focused on the non-physical obligations of the Jew: the obligations of feeling, heart and mind in contrast to those mitzvot that involve the limbs. Pointing to the neglect of this group of mitzvot, he underscored their critical importance.

Rabbi Bachaya’s central focus was on Service of G-d and abiding by His will, and fulfilling the duties of the heart was viewed as the entree to nearness to G-d, the ultimate objective. Understandably, the tenth and last chapter of the book is Love of G-d.

Though emphasizing the importance of rational thought, Rabbi Bachaya’s real goal was the experience of G-d. A systematic, carefully constructed work, Duties of the Heart, has remained to this day a favourite of serious, sensitive students.

His works displayed the rare combination of tremendous emotion, vivid poetic imagination, powerful eloquence, and a penetrating intellect.

Baḥya also composed a number of liturgical poems, some of which have been included in versions of the Machzor, or High Holiday prayer book.

Sources and further reading

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bahya_ibn_Paquda

- https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/112348/jewish/Rabbi-Bahya-Ben-Joseph-Ibn-Pekudah.htm

- https://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/2368-bahya-ben-joseph-ibn-pakuda

- https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/bahya-ibn-pakudah/

- https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/rabbi-bachaya-ibn-pakuda

- https://www.sefaria.org/topics/bachya-ibn-pekuda?sort=Relevance&tab=sources

Rabbi Yehuda HaLevi

Judah ben Samuel Halevi (c. 1075–1141) was the most outstanding Hebrew poet of his generation in medieval Spain. Over the course of some fifty years, from the end of the 11th century to the middle of the 12th, he wrote nearly 800 poems, both secular and religious.

However, because this was a time of intensifying religious conflict characterized by physical, social, and political upheaval, Halevi also sought to develop a reasoned defence of the Jewish religion, which was then under attack on all fronts. Christians and Muslims dismissed Judaism as a superseded religion and reviled its adherents as guilty of both blindness and faithlessness. Those more inclined to philosophy, inside as well as outside the Jewish faith, found many more points to contest. For some, these included even the most fundamental teachings of Judaism, such as God’s creation of the world and his involvement in the affairs of mere flesh and blood, which they regarded as perplexing, at best, or incredible altogether.

In addition to his poems, Halevi is renowned for his very influential philosophical treatise, the Kuzari, originally written in Arabic but later translated into Hebrew. Halevi structured this work around the accounts of a heathen tribe, the Khazars, whose king and people converted to Judaism; the Kuzar iconsists of a dialogue between a Jewish sage and the king of the Khazars.

Sources and further reading

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Judah_Halevi

- https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/111871/jewish/Rabbi-Judah-Halevi.htm

- https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/halevi/

- https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/judah-halevi/

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Judah-ha-Levi

- https://aish.com/yehuda-halevi-a-glittering-jewel-of-the-golden-age/

- https://thegreatthinkers.org/halevi/biography/

- https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/yehudah-halevi

- https://www.sefaria.org/topics/yehuda-halevi?sort=Relevance&tab=sources

Jews were connected to their fellow Jews worldwide and this enabled them to succeed in developing Spain via trade. Additionally, since the Muslim and Christian worlds were engaged in war and were not communicating directly, the Jews served as middlemen, fostering trade throughout the Far East, Middle East, and Europe.

Muslim rulers implemented a system known as dhimmi, which provided certain protections and rights to Jews as “People of the Book,” albeit as second-class citizens. While there were occasional outbreaks of violence and persecution, particularly during times of political instability, Jews generally lived in peace and prosperity, coexisting alongside Muslims and Christians in a multicultural society.

The Tide Turns

In 1066 – only 11 years after Rabbi Shmuel Hanagid’s passing – a Muslim mob stormed the royal palace in Granada and murdered his son, the vizier Rabbi Yosef Hanagid. They also massacred most of the city’s Jewish population. Accounts of the Granada Massacre state that more than 1,500 Jewish families were murdered in just one day.

In 1090 the situation deteriorated further in the Muslim-controlled areas with the invasion of the Almoravids, a Muslim sect from Morocco. Even under the Almoravids, things were somewhat bearable for the Jews. However, in 1148, when the more extreme Almohads invaded Spain, Jews were forced to flee, be killed, or accept Islam. The Almohads confiscated Jewish property in Spain, closed the famous Jewish educational institutions, and destroyed synagogues throughout the land. Among the Jews who fled from the Almohads was the great rabbinical scholar, the Rambam (Maimonides) and his family.

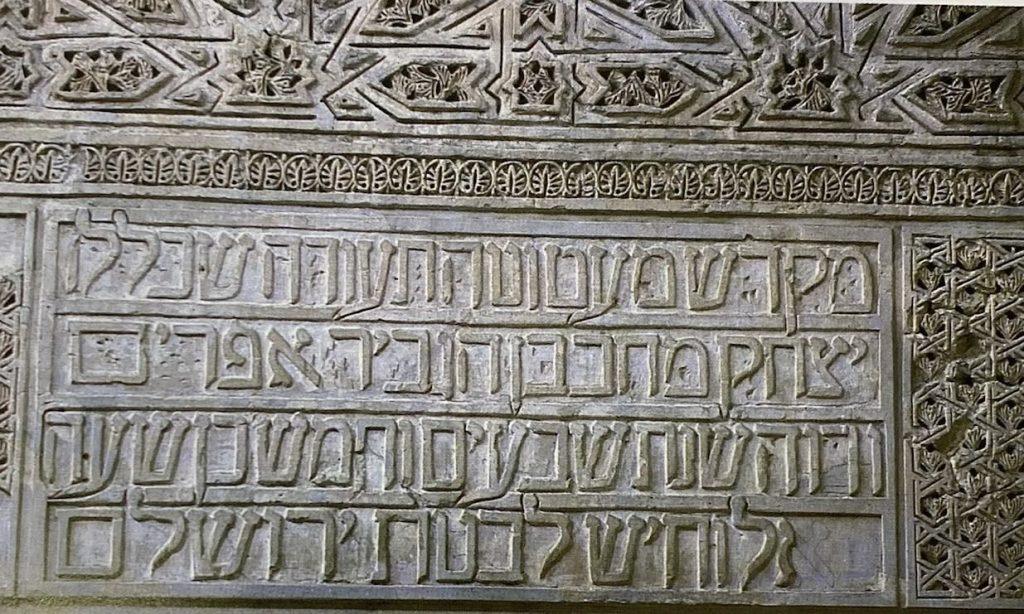

Seville. Treasure’ (collection of relics and ornaments) of the Cathedral. Key to the Jewish quarter which, according to tradition, was offered by the Jews to Fernando III of Castile when he conquered the city. On one of the movable circles, beside the main ring, it bears a Hebrew inscription that reads: “The King of Kings shall open, the King of all the Earth shall enter” On the wards, surrounded by pierced work, it contains the Castilian inscription: ‘DIOS ABRIRA, REY ENTRARÁ (‘GOD SHALL OPEN, KING SHALL ENTER’).

Christian Rule

Early Christian rule in 11th century Spain was tolerant but short-lived. Alfonso VI, the conqueror of Toledo (1085), was tolerant and benevolent toward the Jews. He even offered them full equality with Christians and the rights granted to the nobility, hoping to draw the wealthy and industrious Jews away from the Moors. To show their gratitude to the king for the rights granted them and their enmity towards the Almohads, the Jews volunteered to serve in the king’s army. There were 40,000 Jews who served, distinguished from the other combatants by their black-and-yellow turbans. The king’s favouritism toward the Jews became so apparent that Pope Gregory VII warned him not to permit Jews to rule over Christians.

At the beginning of the thirteenth century, the condition of the Jews once again worsened. Catholics started antisemitic riots in Toledo in 1212, which spread with attacks against Jews across Spain.

The Church became increasingly and openly antagonistic towards the Jews. A papal bull issued by Pope Innocent IV in April 1250 further prohibited Jews in Spain from building new synagogues without special permission, outlawed conversion to Judaism and forbade many forms of contact between Jews and Christians. Jews were also forced to live separately in the Juderia (Jewish ghettos).

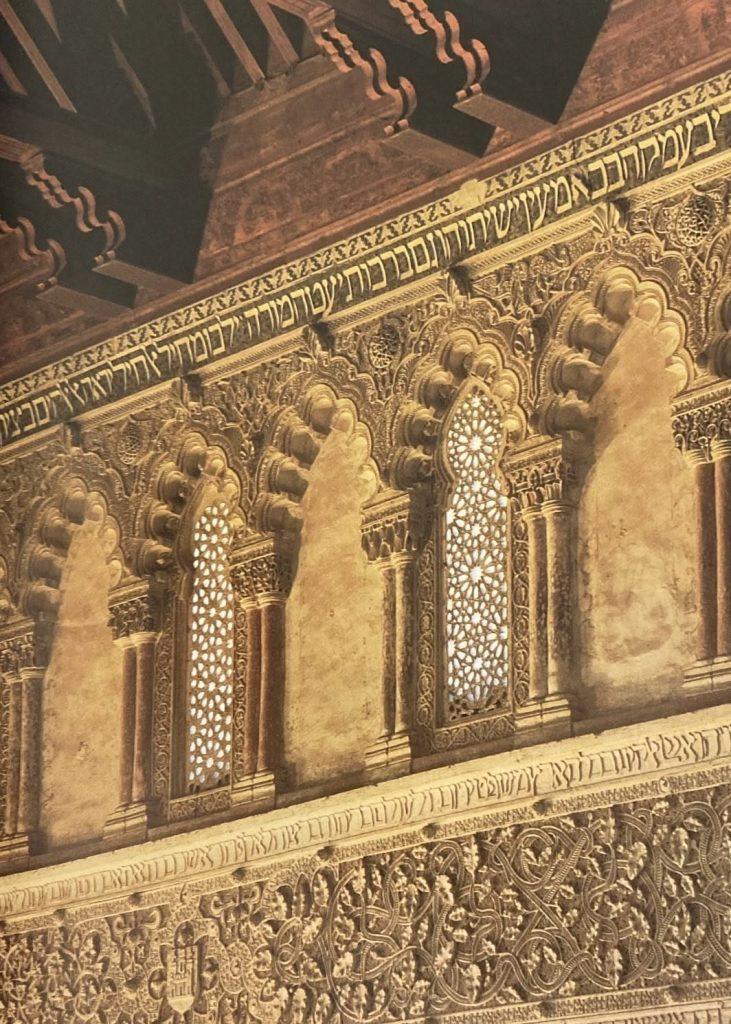

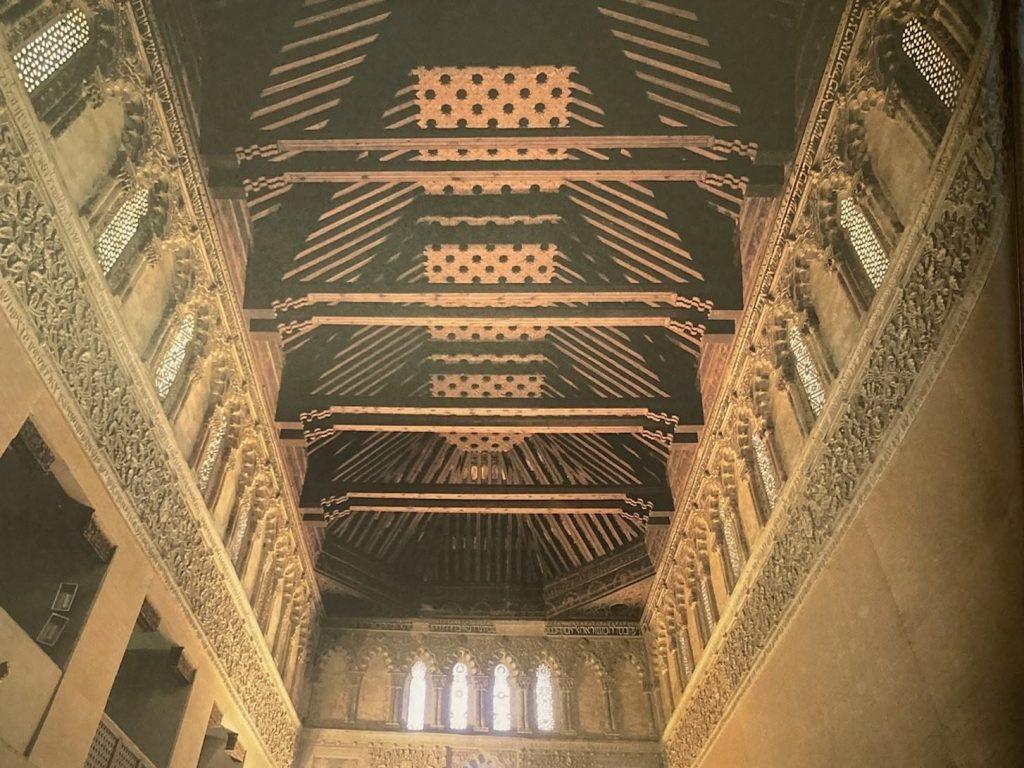

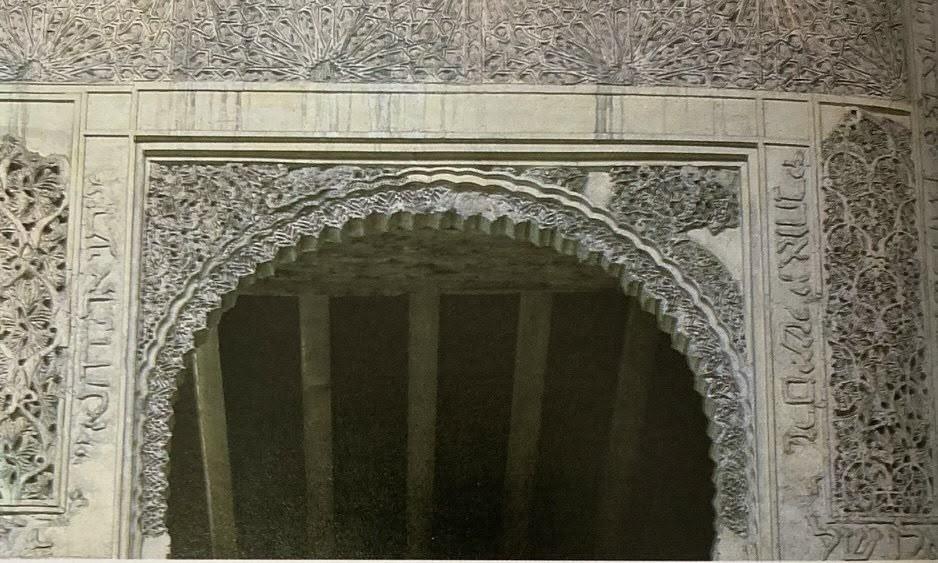

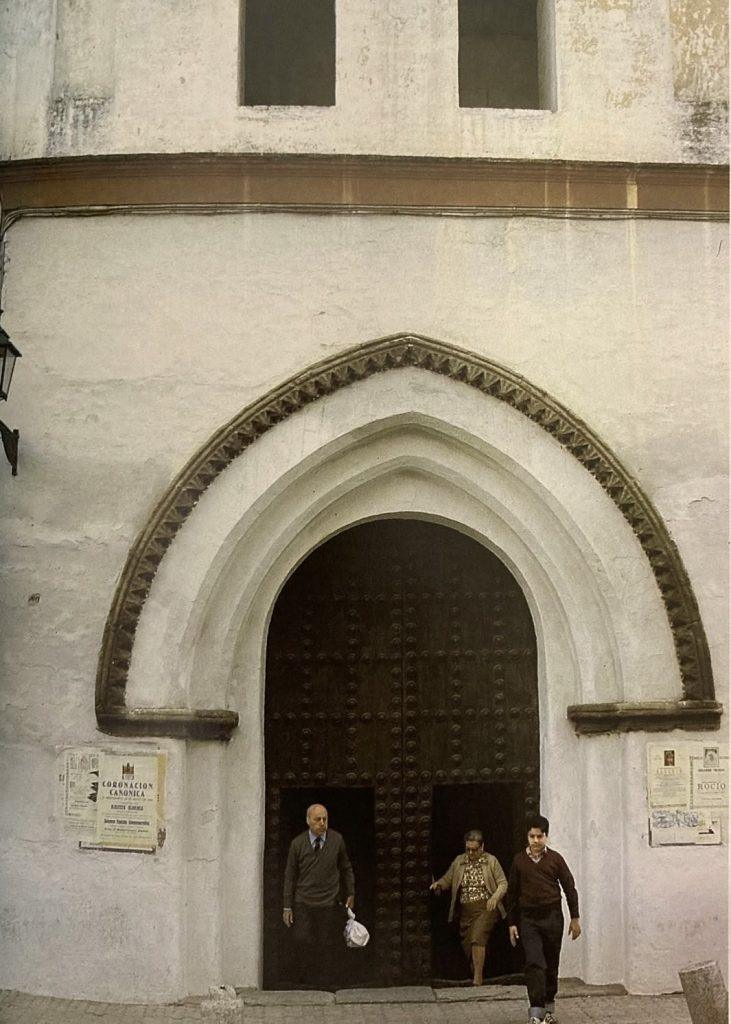

Toledo. The synagogue is called Santa Maria la Blanca. This beautiful synagogue, which was built by Joseph ibn Shoshan, almojarife (royal tax collector) to Alfonso VIII of Castile (12th century), became the church of Santa Maria la Blanca as a result of the preaching of St.Vincent Ferrer around 1411. In 1851 it was declared a national monument

Inquisition

The marriage of Ferdinand V of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile in 1469 unified Spain and transformed it from a combination of provinces into a powerful kingdom. Isabella was a fervent Catholic and, in partnership with the pope, set up an Inquisition in 1478 to find and fight heresy in the Christian world. The royal decree that founded the Inquisition explicitly stated that the Inquisition was instituted to search out and punish converts from Judaism who transgressed against Christianity by secretly adhering to Jewish beliefs and observing Jewish laws. No other group was mentioned, making it clear that Jews were the primary target of this decree.

In 1483, Tomas de Torquemada was appointed Grand Inquisitor. From this point onward, the Inquisition became infamous for its brutality. Torquemada established procedures for the Inquisition, where a court would be installed in a new area, and residents were encouraged to report information regarding Jews observing Jewish practices.

Evidence accepted included the absence of chimney smoke on Saturdays (a sign the family might secretly be honouring the Sabbath), buying many vegetables before Passover, or purchasing meat from a converso butcher. Then the court would employ physical torture to extract confessions and burn those who would not submit at the stake.

Expulsion

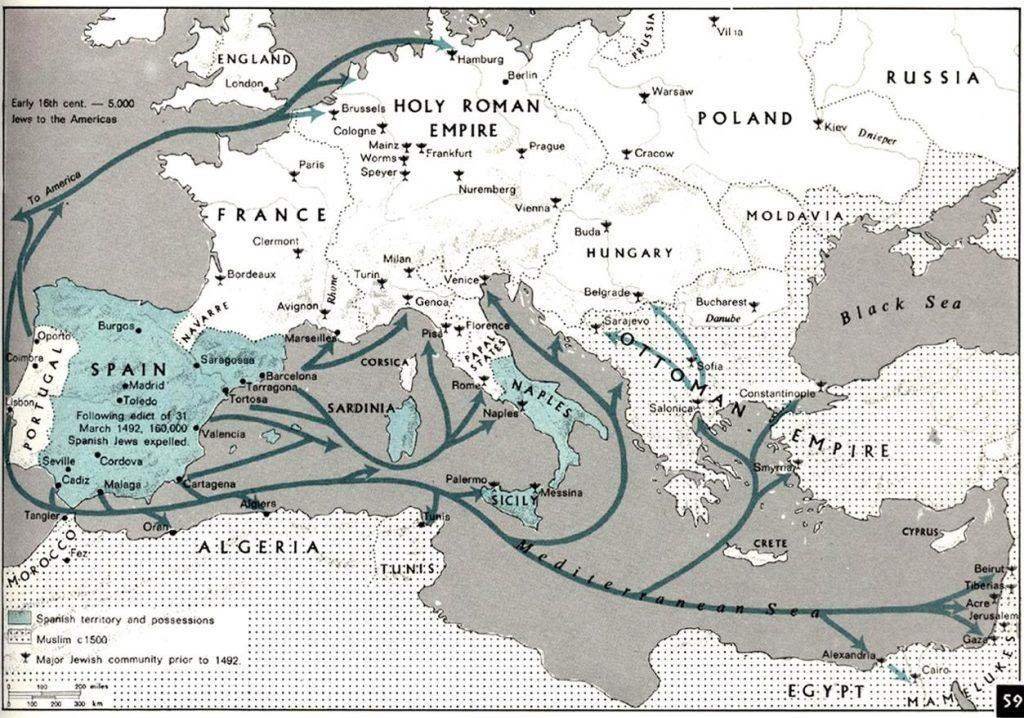

The year 1492 marked the fall of Granada, the last Muslim stronghold on the Iberian Peninsula, and the year Ferdinand and Isabella issued the infamous Alhambra Decree, which ordered the expulsion of Jews from Spain. This time, the monarchs did not target Jewish converts to Christianity but Jews who had never converted.

The main reason stated in the Edict of Expulsion was to prevent Jews from re-Judaizing the conversos (converts). Another factor that certainly played a significant role was that Jewish money was needed to rebuild the kingdom after the costly war against the Muslims. The simplest way to acquire the funds was to expel the Jews and confiscate the wealth and property they would leave behind. (This was a method repeated numerous times during the Middle Ages in Europe, as European countries would expel the Jews in order to remove their debts and take the money from the Jews that were forced out of their country).

The Jews, led by Don Isaac Abarbanel, tried to get the edict revoked. Abarbanel was a great Torah scholar and leading rabbi and had also served as the treasurer of Spain. As the most influential Jew in Spain then, he tried hard to rescind the expulsion order and even offered the monarchs 300,000 ducats for a reprieve. He almost succeeded in getting the monarchs to rescind the edict, but Grand Inquisitor Tomas de Torquemada frustrated his attempt.

Most of the Jews that fled Spain made their way across the border to Portugal. However, only five years later, Portugal forced the choice of conversion or death upon the Jews in its country, and Jews who could get out were on the run again.

The Journey to the Ottoman Empire

Many Sephardic Jews sought refuge in neighbouring regions and countries, including North Africa, Italy, and the Ottoman Empire. The journey to the Ottoman Empire typically involved traveling through North Africa or Mediterranean ports and then crossing into Ottoman territories. Some Jews embarked on perilous sea voyages, while others travelled overland, navigating through various cities and regions along the way.

Once in the Ottoman Empire, Sephardic Jews found relative safety and tolerance compared to the persecution they faced in Spain and other European countries. Sultan Bayezid II issued a decree inviting Jews expelled from Spain to settle in the Ottoman Empire, recognizing their skills, contributions, and potential economic benefits.

Consequences

The expulsion of Jews from Spain had profound consequences, not only for the Jewish community but also for the country as a whole. It led to the loss of valuable intellectual and economic assets, as well as the cultural diversity that had once defined Spanish society. The impact of this expulsion reverberated throughout Europe and beyond, shaping the course of Jewish history and influencing the development of Western civilization.

Professor Norman Roth, points out that in the 12th century A.D. the Sephardim made 90% of world Jewry

Sources and References

https://aish.com/the-tragic-history-of-the-jews-of-spain/

https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/spain-announces-it-will-expel-all-jews#

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Expulsion_of_Jews_from_Spain

https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/inquisition-in-spain/

https://www.pbs.org/wnet/exploring-hate/2022/07/26/expelled-from-spain-july-31-1492/

Additional Resources

The Mezuzah in the Madonna’s Foot: Oral Histories Exploring Five Hundred Years in the Paradoxical Relationship of Spain and the Jews

Alexy, Trudi. New York: Simon & Schuster

The Jews of Spain: From Settlement to Expulsion

Assis, Yom Tov. Jerusalem: The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 1988.

Visgoths and Muslims in medieval Spain: cooperation and conflict

Roth, Norman, 1994, Jew, Leiden: Brill